2025. “Does the United Nations Need Agents? Testing the role of AI agent generated personas in humanitarian action.” Working Paper, UNU CPR, New York.

This paper illustrates a case study with two AI agent generated persona systems, one called “Ask Amina” and the other “Ask Abdalla.” The first is designed to create an accurate digital representation of a refugee living in a camp in Chad. The second creates a digital replica of a combatant leader in the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a group active in the southeastern part of Sudan from which many refugees are fleeing. Both systems combine digital avatars with large language models (LLMs), retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) and AI agent curated knowledge bases specifically designed to maximize the representativeness of each persona.

The effectiveness of Amina’s representation is measured by comparing “her” responses to survey questions against those provided by actual members of the refugee population. A sample of a negotiation with Abdalla, as well as a conversation between Amina and Abdalla, are qualitatively assessed. The experiment methodology and results are described in the case study section of this paper with further details in the appendix. Both personas can be experienced and tested at askamina.ai. Readers are invited to interact with either persona on any desired subject.

The primary objective of Ask Amina is to enable humanitarian and relief workers to ask questions about refugee experiences, needs, and sentiments, and receive responses that closely mirror real refugee perspectives. The objective of Ask Abdalla is to enable diplomats, and mediators to practice their skills with a persona that responds in ways consistent with a real combatant’s known behavioural patterns. The two personas are also put in conversation with each other as a preliminary test of a virtual AI-based community dialogue simulation.

AI Agents in Global Governance: Digital Representation for Unheard Voices

Artificial intelligence is reshaping multilateral decision-making by giving voice to previously unheard stakeholders. Based on my recent book, Political Automation: An Introduction to AI in Government and Its Impact on Citizens (Oxford University Press, 2025), I argue that AI agents can help international organizations better incorporate marginalized communities into global governance frameworks.

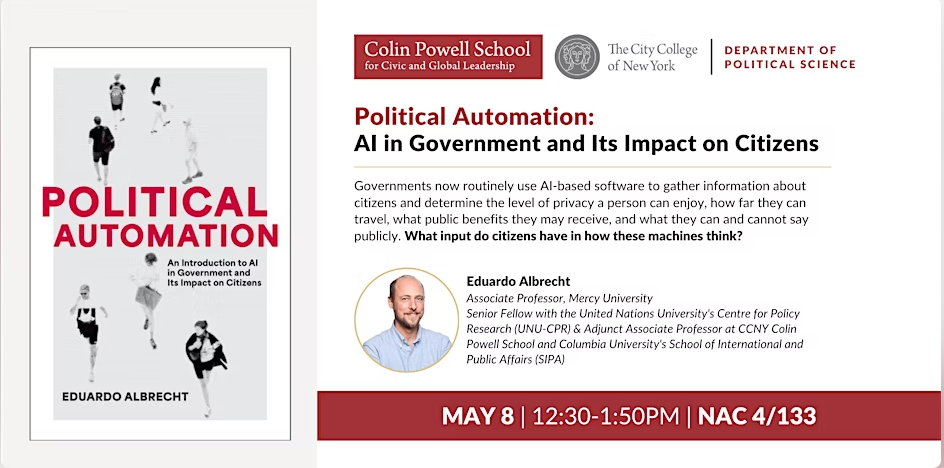

Political Automation Book Launch at Colin Powell School for Civic & Global Leadership

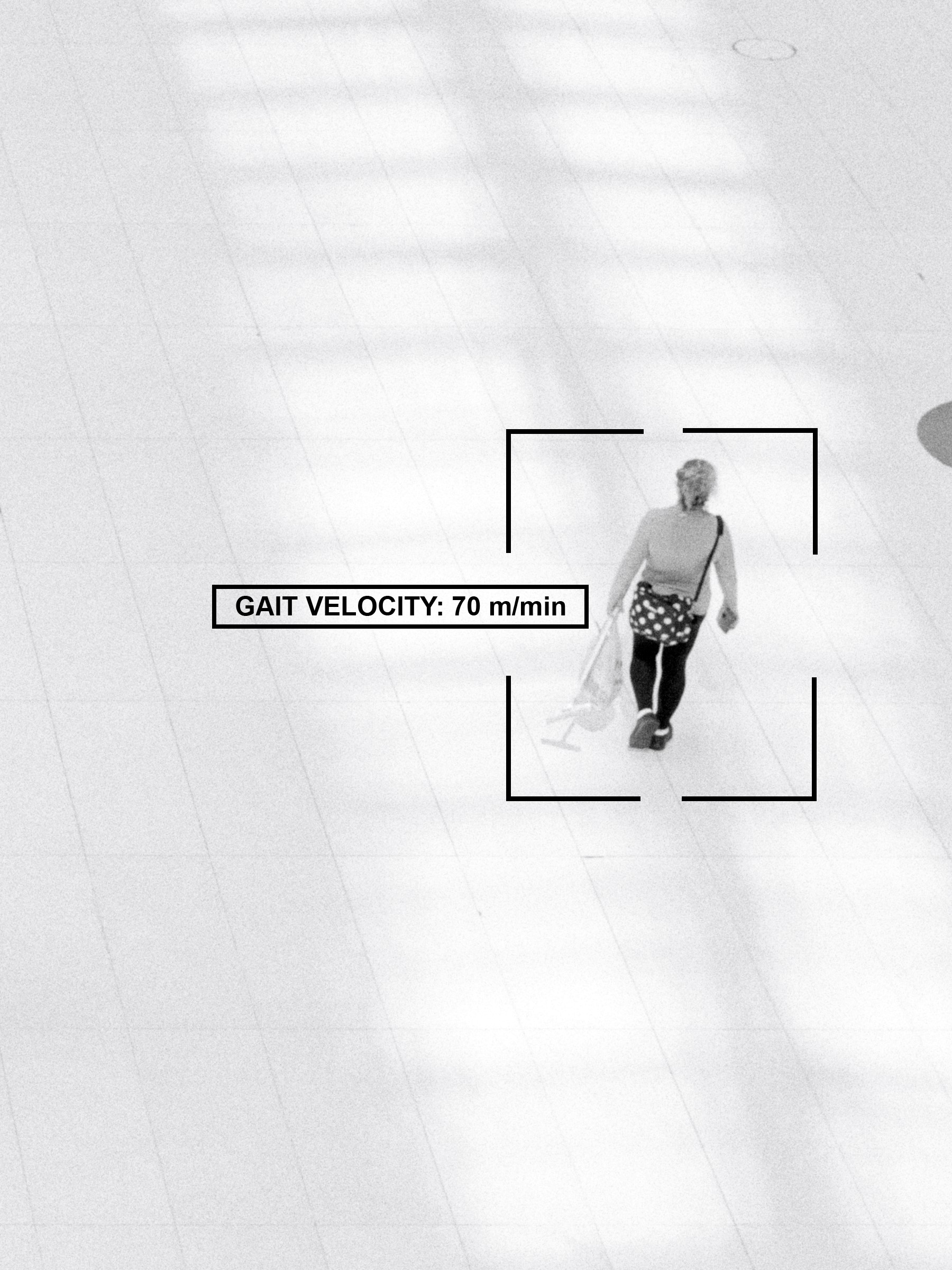

Governments now routinely use Al-based software to gather information about citizens and determine the level of privacy a person can enjoy, how far they can travel, what public benefits they may receive, and what they can and cannot say publicly. What input do citizens have in how these machines think?

Book your free tickets at the link below for the launch of Political Automation: AI in Government and its Impact on Citizens at the Colin Powell School for Civic & Global Leadership on Thursday, May 8 · 12:30 - 1:50pm EDT.

Reboot Democracy Blog - Branching Out: A Third Legislative Chamber for the AI Age

The proliferation and collection of large amounts of citizens’ data has led to the rise of "political machines" – AI systems used in government to make decisions around resource allocation. Political anthropologist Eduardo Albrecht argues that establishing a "Third House" – a new legislative body specifically designed to oversee the deployment and operation of political machines – could enable citizens to meaningfully engage with and oversee the AI tools used by their government.

Read the full blog here.

John Cabot University Interview - Political Automation: Alumnus Eduardo Albrecht Publishes New Book on AI

JCU alumnus Eduardo Albrecht (class of 1999, International Affairs and History) has recently published his new book, titled Political Automation: An Introduction to AI in Government and Its Impact on Citizens (Oxford University Press, 2025), which investigates the increasing governmental use of AI and theorizes the changing role of citizens in policy making.

Read the full interview here.

AI in Government: A SIPA News Q&A with Political Anthropologist Eduardo Albrecht

In his new book, Political Automation: An Introduction to AI in Government and Its Impact on Citizens (Oxford University Press), Eduardo Albrecht, a SIPA professor and political anthropologist, examines how states deploy AI to make consequential decisions about their citizens. He proposes a revolutionary “Third House” of government—a virtual legislative chamber dedicated to AI oversight and governance.

Albrecht, who is also a senior fellow at the United Nations University’s Centre for Policy Research, draws on extensive fieldwork and ethnographic interviews with rights activists to document both the current state of algorithmic governance and emerging citizen responses.

In this SIPA News Q&A, Albrecht discusses the profound implications of AI-mediated governance, the risks of surrendering human judgment to automated systems, and his vision for preserving citizen agency through the creation of “digital citizens” who would represent citizens’ interests in an increasingly automated public sphere.

Read the full interview here

IPI Global Observatory Blog - Political Machines: The Rise of Automated Governance and the Global Challenge to Citizens’ Rights

In December 2023, the United Nations (UN) Secretary-General’s High-level Advisory Body on Artificial Intelligence published its interim report highlighting the need for stronger regulatory frameworks around AI systems. In September 2024, at the UN Summit of the Future, the Global Digital Compact was adopted, establishing crucial guardrails for AI technologies.

Read the full blog here.

Cybersecurity Threats to Global Peace - UNSCripted Podcast

In June I was invited by Damilola Banjo to appear on the podcast UNSCripted by PassBlue, an independent media platform dedicated to reporting on issues related to the United Nations and global diplomacy.

The podcast featured an interview with UN Ambassador Joonkook Hwang, the permanent representative of South Korea (holders of the Security Council presidency for June).

The theme under discussion was the threat of cybersecurity to global peace. I was asked to provide context on emerging technologies and their impact on international governance.

The conversation addresses: Why South Korea is making cybersecurity a Security Council matter at this time; why cyber-attacks were becoming North Korea’s weapon of choice; and what changes we are like to see in the Security Council.

Read the full interview here.

Listen to the podcast here.

Perception, Foreign Policy, and US Election Politics: Are We Sleepwalking Into World War III?

Event hosted by the School of Social and Behavioral Science at Mercy University: ‘Perception, Foreign Policy, and US Election Politics: Are We Sleepwalking Into World War III?’ on March 21st, 2024 at 12:00 noon.

Discussion with our guest speakers: Dr. Lucio Martino, former Italian defense consultant and a news contributor for the Italian Mediaset networks, and Kate Tedesco, Adjunct Professor and Criminal Justice Program Coodinator, School of Social and Behavioral Science.

2024. Disinformation and Peacebuilding in Sub-Saharan Africa: Security Implications of AI-altered Information Environments.

Artificial intelligence (AI) capacity and use has developed very rapidly over the last five years. As the international community increasingly focuses on establishing global governance of AI to harness its opportunities while mitigating its risks, concerns regarding AI's impact on peace and security have grown.

This concern is particularly associated with recent advancements in generative AI, a subfield enabling the creation of diverse content types such as text, images, videos, and audio, using new AI tools which have begun to be linked to increases in disinformation campaigns, cybersecurity threats, hate speech towards women and minorities, and other conflict drivers.

A new UNU-CPR report explores the way in which AI technologies as they currently stand impact peace and conflict, and what methods might be used to mitigate their adverse effects - through the development of better tools and the inclusion of peace and conflict considerations in AI governance frameworks.